The 10 Best NFL Players of All Time — Football Legends From Montana to Brady

February 18, 2026

The question of the best NFL players of all time is less a mathematical exercise than a debate about eras, roles, and impact. A quarterback from the 1950s played under different rules than a superstar of the 2010s, and even within a single era, responsibilities differ: a cornerback is measured by passes prevented, a running back by yards and efficiency, a quarterback by decisions, points, and— in public memory—titles. That is precisely why all-time rankings are also a look at how football defines “greatness”.

This article takes a broad thematic look at four motifs that run like a common thread through NFL history: the birth of modern TV football, dynasties and iconic plays, defensive revolutions, and the era of quarterback reference points. It concludes with a selection of ten players who repeatedly appear in many serious debates and selection teams—without claiming to end the discussion, but to structure it clearly.

IMAGO accompanies such sports stories visually: as an international content and image platform, IMAGO works with a global network of partner photographers, agencies, and archives. For media outlets, agencies, brands, creators, blogs, NGOs, and educational institutions, this mainly means: images can be clearly licensed—depending on medium, term, and context of use—without confusing usage rights with ownership.

We advise you on the right images for NFL coverage—including tailored media packages.

We advise you on the right images for NFL coverage—including tailored media packages.

Why “the greatest of all time” is hard to determine in the NFL

Anyone comparing NFL eras is also comparing rulebooks, pace of play, and season lengths. Statistics explode in pass-heavy periods, while earlier decades were dominated by a run-first logic. Add to that: not every position has equally visible metrics. A defensive end can shape a game without ever touching the ball—and still fundamentally change an offense.

For a ranking to be more than just “counting rings,” it needs multiple criteria that together create a transparent perspective. Many historical debates therefore revolve around three pillars: dominance in one’s era, awards/selection teams, and demonstrable influence on tactics or a position. A key anchor point is the official NFL 100 All-Time Team, published for the league’s 100th anniversary as a selection of the 100 greatest players.

IMAGO / Newscom World / Creative close-up detail of the Wilson Duke football for the NFL’s 100th anniversary.

For the selection in this article, a pragmatic yardstick therefore applies:

- Career impact: Was the player a reference point at his position for years?

- Peak performance: Are there peak seasons or playoff moments that are considered the standard?

- Recognition: Hall of Fame, all-time teams, MVP/All-Pro level—depending on position.

- Context resilience: Does the argument still hold when you factor in rules and team environment?

With this framework, the history can be told in stages—and that is exactly where the defining moments begin.

1958 – Johnny Unitas and the beginning of the modern NFL myth

If a single game works as the cultural starting point of the NFL narrative, it is the 1958 NFL Championship Game. It was the first NFL game decided in sudden-death overtime—and it made Johnny Unitas the face of a new, nationally recognized football era.

Unitas’ late-drive architecture—the calm, precise movement of the offense under time pressure—became a prototype for what would later be described as “quarterback management.” Hall-of-Fame narratives emphasize exactly that: the final minute, forcing overtime, and the subsequent march to the decisive touchdown.

What matters here is less nostalgia than mechanics: with Unitas begins the idea that a quarterback not only throws, but organizes game flow—audibles, rhythm, clock management. This is the first bridge to later icons like Montana, Manning, and Brady: all of them stand, in different ways, in that lineage.

1981–1989 – Montana, “The Catch,” and the 49ers as a dynasty narrative

The 1980s shifted the offensive coordinate system—not only through more passing, but by making timing, spacing, and yards after catch a core principle. The iconic marker is “The Catch” in the 1981 season’s NFC Championship Game: Joe Montana throws, Dwight Clark catches—and the 49ers advance to the Super Bowl.

This moment appears in many retrospectives because it bundles two things: the end of a defensive era (Dallas’ dominance) and the beginning of a system later generalized as West Coast thinking. Montana became a symbol of precision under stress—a reputation built not only on single plays, but on repetition in the biggest moments.

The second dynasty moment follows in 1989 in Super Bowl XXIII: San Francisco trails late, gets the ball deep in its own territory, and marches 92 yards for the game-winner. The drive—finished by a touchdown pass from Montana to John Taylor—remains a textbook example of situational playcalling and nerve.

IMAGO / PCN Fotografie / Joe Montana, quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers, in action against the Cincinnati Bengals during the 1989 Super Bowl.

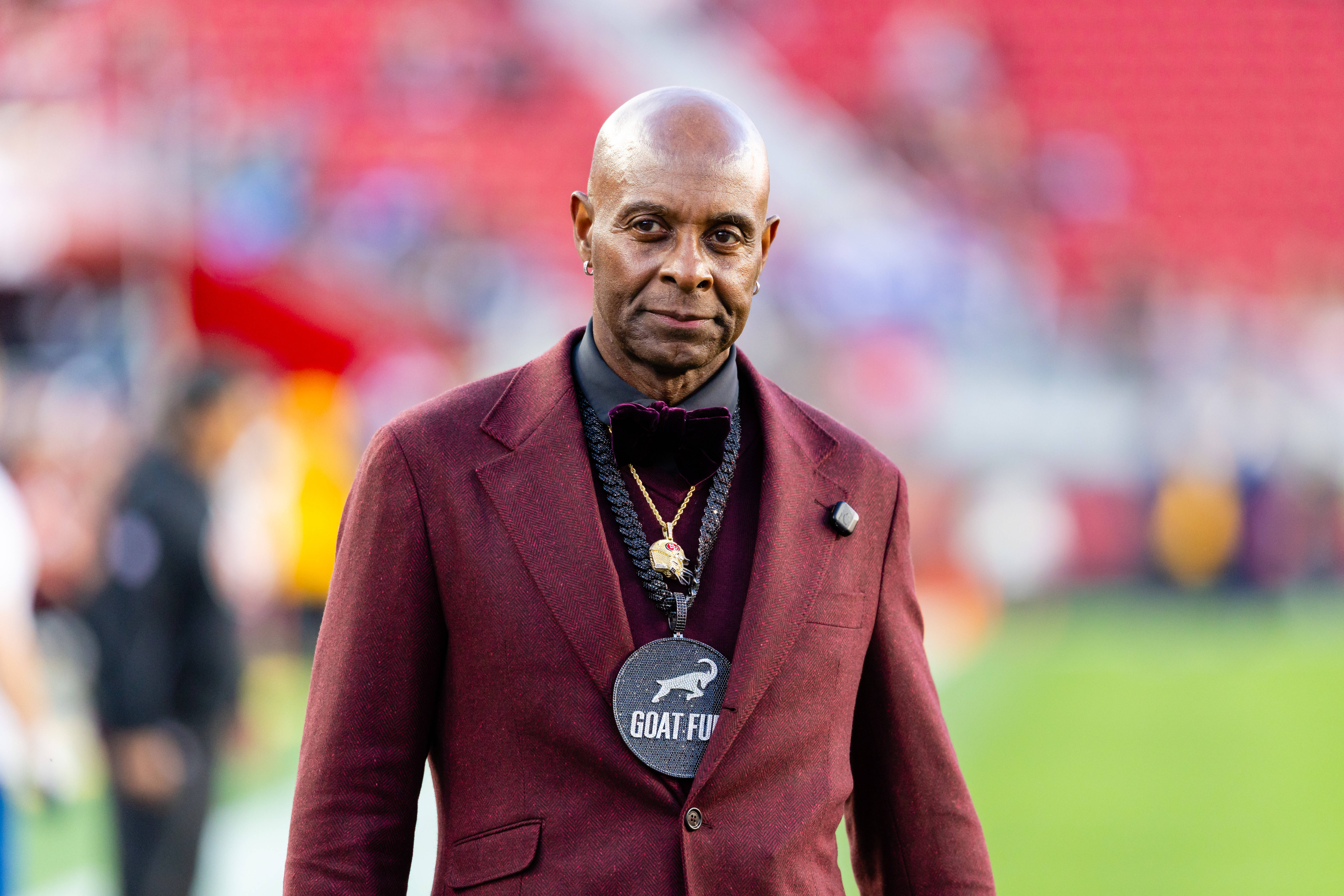

And then there is Jerry Rice, who completes the “Montana narrative” on offense. The Hall of Fame lists Rice as the holder of virtually all key receiving records—including 1,549 receptions and 22,895 receiving yards—and classifies him as the most productive wide receiver in NFL history.

That Rice is still being used as a public figure of the league in 2026 (for example as a coach in a Pro Bowl-style format) also shows how enduring his status as a reference point has remained.

The running back line: Jim Brown and Walter Payton as a counter-model to the passing boom

The NFL likes to tell its story through quarterbacks—but historically, greatness was often also about physical dominance in the running game. Jim Brown is the archetype here: a short career, but with a density of league leads and awards that remains rare. The Pro Football Hall of Fame lists Brown’s record-book standing from his era, including eight seasons as the rushing leader (1957–1961, 1963–1965) and 12,312 rushing yards in nine years.

What matters about Brown is also perspective: many of his records were set in a time with fewer games per season and defensive fronts explicitly built to stop him. His case is therefore not “volume,” but dominance relative to the league—a criterion that often carries more weight in era comparisons than raw totals.

Walter Payton stands in the same tradition—but with a different profile: versatility. The Hall of Fame emphasizes his total-touchdown distribution (rushing/receiving/passing) and points to the legendary game with 275 rushing yards in 1977, a record that stood for more than two decades.

At the same time, Hall-of-Fame history documents Payton’s then-career records, including 16,726 rushing yards and enormous workload figures.

In the broader history, Brown and Payton are therefore more than “best runners”: they represent two types of greatness—immediate superiority and long-term all-around reliability—and provide the counterpoint to the later passing explosion.

Defense that rewrites the rules – Lawrence Taylor and Reggie White

You can also read NFL history as a reaction by defense to offensive trends. Lawrence Taylor marks a point at which pass rush is not just part of the defense, but its identity-defining center. The Hall of Fame describes 1986 as Taylor’s statistically strongest season—including 20.5 sacks—and frames it as the year he was voted NFL MVP (a rare exception for a defensive player).

The tactical core is this: with Taylor, edge play becomes so dominant that offenses must adapt protection schemes. Tight ends stay in to block more often, running backs chip, quarterbacks shorten reads. That is “impact” in the literal sense: not as a highlight, but as a change to standard answers.

Reggie White complements this axis in a different way. His career is often told through sack numbers—the Hall of Fame cites 198 and notes that he was the all-time leader at the time of his retirement.

At least as defining was White’s role in the era of modern free agency: NFL retrospectives describe his move to Green Bay as an early, particularly significant free-agent move—made visible by his impact there, including 68.5 sacks during his Packers years.

Together, Taylor and White show that all-time arguments are not built only on titles. They also emerge when a player forces the NFL to define a new normal—whether in protection, roster building, or play design.

The quarterback reference points – Peyton Manning and Tom Brady

If Unitas opens the myth and Montana condenses it into dynasty, then Manning and Brady split the modern era into two storytelling modes. Peyton Manning is the prototype of the regular-season architect: the Hall of Fame explicitly summarizes him as a two-time Super Bowl champion and five-time MVP.

That five AP MVP awards are the record is also historically anchored in NFL coverage.

Manning’s case is rooted in control: pre-snap reading, audible economy, timing concepts. He represents an NFL in which the quarterback often gives the final authorization to the play at the line of scrimmage—and in which the boundary between playcaller and executor blurs.

Tom Brady is more strongly the postseason reference in public memory. Pro-Football-Reference lists his headline numbers that constantly recur in GOAT debates: 7× Super Bowl champion, 5× Super Bowl MVP, 3× AP MVP, plus years of Pro Bowl and All-Pro presence.

The symbolic Brady moment remains Super Bowl LI on February 5, 2017: New England trails 28–3, forces overtime, and wins 34–28—the first Super Bowl decided in overtime.

Games like this are risky as the sole yardstick, but they help explain why Brady is often read in rankings as a “defining winner under pressure”—regardless of how one weighs team context and coaching.

IMAGO / Newscom World / New England Patriots vs. Atlanta Falcons, Tom Brady holds the Lombardi Trophy aloft and wins his fifth Super Bowl title as the New England Patriots defeat the Atlanta Falcons 34–28 in Super Bowl LI at NRG Stadium in Houston, Texas, on Sunday, February 5, 2017.

Deion Sanders and the art of preventing throws

An all-time piece needs at least one cornerback, because passing offense cannot be evaluated sensibly without pass prevention. Deion Sanders’ case is twofold: athletically as an elite cover corner, culturally as a figure who gave the position visibility. The Hall of Fame lists him as a two-time Super Bowl champion (XXIX, XXX), anchoring his role in two different dynasty contexts.

Add to that the symbolism of selection teams: the NFL reported in 2019 that Sanders was named to the NFL 100 All-Time Team as the first defensive back—an indicator of how highly his position and impact were valued in that anniversary selection.

Sanders thus stands for a simple truth in all-time debates: defensive greatness is often prevention, not production. Players who force quarterbacks to avoid one side of the field do not always show up in box scores—but they absolutely show up in game plans.

IMAGO / Icon Sportswire / Former NFL wide receiver Jerry Rice watches before an NFL game between the Seattle Seahawks and the San Francisco 49ers on January 3, 2026, at Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, California.

The 10 greatest NFL players of all time – an overview

This selection brings together players who recur in many all-time discussions and whose cases carry across eras, systems, and positions. It is deliberately cross-positional—and meant as journalistic organization, not a final verdict. (As a frame of reference, there is, among other things, the official NFL all-time team for the 100th anniversary.)

- Tom Brady (QB) – A record-setting title/MVP résumé and a postseason benchmark that is reflected both statistically and narratively.

- Joe Montana (QB) – Dynasty quarterback linked to “The Catch” and late Super Bowl drives as the standard case for “clutch.”

- Jerry Rice (WR) – Receiving records as a long-term benchmark; the comparison point for the position for decades.

- Johnny Unitas (QB) – Key figure of the early TV era; 1958 as a mythic starting point and blueprint for late drives.

- Jim Brown (RB) – Era-dominant in the running game; Hall-of-Fame record book with league leads and then-records as the core argument.

- Walter Payton (RB) – Versatility and career workload; historic records and iconic single games as proof of lasting quality.

- Lawrence Taylor (LB) – Defense as a playmaker: MVP season in 1986 and pass-rush impact that changed protection structures.

- Reggie White (DE) – Sack production plus structural influence in the free-agency era; Hall-of-Fame résumé as a stability anchor.

- Peyton Manning (QB) – Regular-season benchmark with a record number of MVP awards and a clear game-management identity.

- Deion Sanders (CB) – Cornerback as an all-time case: titles, selection-team recognition, and a style that forced offenses to plan around him.

Honorable mentions (kept intentionally brief, because the list would otherwise be twice as long): Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, Ronnie Lott, Aaron Donald, Dan Marino—depending on whether you weight peak, longevity, or positional value more heavily.

IMAGO / Icon Sportswire / Running back Walter Payton (Chicago Bears, 34) with the ball in 1987, Los Angeles Raiders – Chicago Bears 3:6.

Clarifying image rights cleanly: How licensing works at IMAGO in a sports context

When it comes to historic sports legends, in practice it is almost always about editorial use: coverage, retrospectives, dossiers, podcasts with accompanying articles, club or league history, documentaries. The key principle is: a license governs usage, not ownership. Copyright remains with the respective rights holder.

Depending on the image and collection, IMAGO offers Rights Managed (RM) as well as Royalty Free (RF Classic / RF Premium). RM is typically usage-defined (e.g., medium, term, territory), while RF models allow repeated use within the license conditions. For commercial campaigns (advertising, sponsorship, packaging), you also need the appropriate license and—if required—model or property releases; without releases, material is generally only usable editorially.

Purchase paths vary depending on workflow: single licenses in the webshop, credit packs (for recurring needs), or sales-manager consulting for larger volumes and coordinated contract models.

Summary

For decades, the NFL has produced new stars—but the debate about the best NFL players of all time keeps circling back to the same core questions: Was someone outstanding in their era? Did they change the game? And does their benchmark still hold when you consider context, team, and rule evolution?

From Unitas’ 1958 overtime myth through Montana and Rice’s dynasty signatures to Brady’s postseason benchmark, one thing becomes clear: “all-time” is most convincing when it looks not only at numbers, but at impact and repeatability. And that is exactly why images—properly licensed and correctly contextualized—are more than decoration: they are documentary evidence of a sports history that would otherwise only be told.

License Sports Images Tailored to Your Needs

Real-time editorial sports images across all major sports, including football, F1, tennis, and more, plus access to the largest editorial sports archives. Flexible licensing and fast support in Europe and worldwide.

Learn more