The 10 Most Legendary Olympic Moments

The Olympic Games are more than a medal table. In just a few seconds, records can fall, careers can turn, or images can emerge that remain reference points decades later. Precisely because the Games are watched worldwide, individual scenes shape collective memory — regardless of whether they were experienced in the stadium, on television, or rediscovered later in archives.

For media outlets, agencies, brands, creators, NGOs, and educational institutions, this visual language remains relevant today: It is quoted, contextualized, collected in dossiers, or re-framed in features. IMAGO, as an international image and content platform, works with a global network of partner photographers, agencies, and archives — supporting professional image research and licensing for editorial and (under the right conditions) commercial projects.

Our specialists will help you find the right images and define the best licensing options for your project. Share your requirements, and we’ll be in touch shortly.

Our specialists will help you find the right images and define the best licensing options for your project. Share your requirements, and we’ll be in touch shortly.

What makes an Olympic moment “legendary”?

Legendary does not automatically mean “record-breaking.” A moment often becomes historic when it connects several levels: athletic performance, social context, and media distribution. At the Olympics, there is also the official motto, updated in 2021 to “Citius, Altius, Fortius — Communiter” (“Faster, Higher, Stronger — Together”), emphasizing the idea of a shared stage.

In practice, many iconic scenes fall into three categories: records that redefine limits; triumphs that resonate beyond sport; and tragedies that change rules, security concepts, and public memory. This mix explains why “the” top ten moments are never fully objective — and why the examples below read as a thematic overview.

The 10 most legendary Olympic moments at a glance

1) Jesse Owens, Berlin 1936: four gold medals against the spirit of the time.

Owens won four gold medals in Berlin (100 m, 200 m, long jump, 4×100 m). Internationally, his success was also widely perceived as a counterpoint to the Nazi regime’s propagandistic ambitions.

IMAGO / United Archives / Jesse Owens Olympic Games Berlin 1936

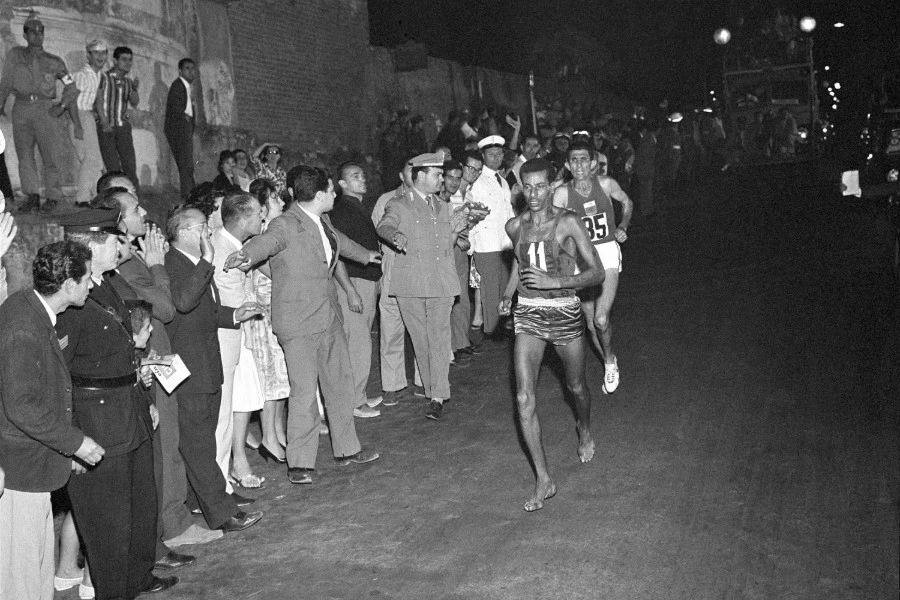

2) Abebe Bikila, Rome 1960: the barefoot marathon — and a world record.

Bikila ran the Olympic marathon barefoot and won in a world-record time of 2:15:16.2. Contemporary reporting also notes that the decision was linked to ill-fitting new shoes.

IMAGO / TT / After 42 km. of marathon the athlete of Ethiopia, Abebe Bikila reached the first the finish line.

3) Tommie Smith & John Carlos, Mexico City 1968: protest on the podium.

At the 200 m medal ceremony, the two U.S. sprinters made a highly visible statement against racism and for human rights — an image that still functions as a reference point for the relationship between sport and activism.

og2IMAGO / Horstmüller / Olympics 1968 in Mexico Tommie Smith

4) Bob Beamon, Mexico City 1968: 8.90 meters that defined an era.

Beamon’s 8.90 m jump broke with the expectations of the time. His world record stood for nearly 23 years (until 1991), and the jump remains the Olympic record.

ography | London 2012IMAGO / WEREK / Bob Beamon (USA)

5) Munich 1972: a terrorist attack — and a break in the Olympic narrative.

The attack on the Israeli team is considered a turning point. The IOC has repeatedly referred to it as the “darkest day” in Olympic history.

IMAGO / Werner Schulze / The Olympic flag hangs at half-mast in the fully occupied Olympic Stadium during the memorial service for the victims of the hostage-taking Athletics Olympic Summer Men's Olympic Games 1972

6) Nadia Comăneci, Montreal 1976: the first “10.0” — and seven perfect scores.

Comăneci received the first perfect 10.0 score in Olympic gymnastics; in Montreal she achieved seven perfect scores in total. She won three gold medals, plus silver and bronze.

IMAGO / WEREK / Nadia Comaneci (Romania) on the uneven bars

7) “Miracle on Ice,” Lake Placid 1980: USA defeats the USSR 4–3.

On February 22, 1980, the U.S. ice hockey team beat the heavily favored Soviet Union 4–3 — a moment widely understood as both sporting and politically charged in its era.

IMAGO / Sven Simon / Celebration USA The US ice hockey team became Olympic champions at the 1980 Olympic Games in their home Lake Placid, defeating the seemingly invincible opponent USSR.

8) Muhammad Ali, Atlanta 1996: lighting the cauldron — an image of vulnerability and presence.

Ali lit the Olympic flame at the opening ceremony; many accounts point to the visible effects of Parkinson’s disease, contributing to the scene’s lasting symbolic power.

2IMAGO / Zuma Press Wire / In 1996, Muhammad Ali shocked the world at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games

9) Michael Phelps, Beijing 2008: eight gold medals in one Summer Games.

Phelps won eight gold medals in Beijing and later built his Olympic total to 28 medals, including 23 gold.

.webp?width=760&height=507&name=sorry-i-can-t-help-with-that%20(1).webp) IMAGO / Xinhua / Olympic champion 2008 in the 100m butterfly - Swimming Olympic Summer Games Men's Olympic Games 2008, Summer Games, 100m butterfly, Butterfly Single image Beijing Joy, Enthusiasm

IMAGO / Xinhua / Olympic champion 2008 in the 100m butterfly - Swimming Olympic Summer Games Men's Olympic Games 2008, Summer Games, 100m butterfly, Butterfly Single image Beijing Joy, Enthusiasm

10) Usain Bolt, London 2012: 9.63 seconds as an Olympic benchmark.

Bolt won the 100 m in 9.63 seconds, setting an Olympic record. He also won both the 100 m and 200 m at three consecutive Olympic Games (2008, 2012, 2016).

IMAGO / PCN Photography | London 2012 Olympics Track and Field, Usain Bolt after winning the gold medal for Jamacian in the 4X100m relay at the Olympic Summer Games, London 2012.

With that framework in place, four thematic threads emerge — and they run through many Olympic “key scenes.”

Records as Markers of Time: Numbers, Conditions, Meaning

Records feel objective because they are numbers. At the same time, they are always stories about conditions: altitude, heat, equipment, timing technology, and competitive pressure. That makes Olympic records useful “anchors” — in sports journalism and in visual archives.

Bob Beamon in 1968 is a textbook example. His 8.90 m jump was not only gold but a statistical outlier: The gap to the previous record was so large that “Beamonesque” entered common language. The fact that the world record lasted until 1991 reinforces the moment as an epoch marker.

From track and field, the line leads directly into the gym. Nadia Comăneci demonstrated in 1976 how a rulebook can reach the limits of its representation: The perfect 10.0 was theoretically possible, but the scoreboard was not designed for it — a technical footnote that has since become a symbol of dominance. The fact that Comăneci earned seven perfect scores in Montreal and won multiple medals underscores that it was not a one-off: It was repeatable precision.

In modern times, Michael Phelps in 2008 represents a different form of record — not one number, but a sequence. Eight gold medals in Beijing remain an extraordinary concentration of top-level performances; his career total of 28 Olympic medals (including 23 gold) has made him a benchmark in discussions of dominance and longevity in elite sport.

IMAGO / ZUMA Press Wire | USA’s Michael Phelps swims in the Men´s 200m Butterfly at the 2008 Beijing Olympics 2008 in Beijing, China. Phelps finished in 1st place winning his fourth gold.

And then there is Usain Bolt: His Olympic record of 9.63 seconds in London 2012 shows how a record can simultaneously become an image icon — the finish-line camera turning into a global stage for a brief, widely shared sequence. Bolt’s achievement of winning the 100 m and 200 m at three consecutive Olympic Games (2008, 2012, 2016) adds historical weight.

The common denominator in these records is therefore not just the number. It is the repeatability of the story: A performance becomes a reference when it can consistently serve as a “before/after” moment in tables, timelines — and images.

Triumph as a social signal

After the records, the next question almost automatically follows: What does the moment stand for — beyond the sport itself? Some of the most enduring Olympic images are enduring precisely because they connect athletic achievement with broader social meaning.

That begins early in the modern media history of the Games with Jesse Owens in 1936. Owens won four gold medals in Berlin; sources emphasize that his victories visibly contradicted the Nazi regime’s attempt to stage “superiority.” From a journalistic perspective, the distinction matters: Owens’ performance was a sporting fact — the political impact came from the context in which it occurred and was disseminated.

Only 24 years later, a triumph shifts the focus to a different part of the world: Abebe Bikila in 1960. His barefoot marathon run, the world-record time of 2:15:16.2, and the narrative that ill-fitting shoes played a role, became a signal of the growing international visibility of African distance runners. The scene remains doubly usable: as sports history and as a story about global perception.

In 1968, again in Mexico City, the level shifts further. Tommie Smith and John Carlos used the medal podium as a platform for a human-rights message. Later institutional reflections show how strongly this scene shaped debates about political expression at the Olympics — and how its effect continued through reception, not just the moment itself.

This thematic thread leads logically to Muhammad Ali in 1996. Ali lit the Olympic flame in Atlanta; reporting frequently notes that his Parkinson’s disease was visible, and that the scene is often read as a symbol — not of a record, but of public presence despite physical limitation.

Together, these examples show: Triumph can be a result, a context, or a gesture. In image selection, these layered moments are often exactly what editorial teams need for background pieces, anniversaries, and social debates.

When an event becomes bigger than the tournament

After records and symbolic images comes a third category that often revolves around team dynamics: the underdog moment. The Olympics are not only individual competition but also a projection surface for collectives — nations, generations, styles of play.

The most famous example is the “Miracle on Ice” at the 1980 Winter Games in Lake Placid. On February 22, 1980, the U.S. ice hockey team beat the favored Soviet Union 4–3. Sources emphasize that the outcome was perceived as far bigger than sport at the time because it occurred during the Cold War.

Visually, this category is especially interesting: Unlike an individual record, there is rarely “the one” definitive winner photo. More often, it is a sequence — bench reactions, goalmouth scenes, celebrating players, scoreboard frames, crowd emotion. The event is the collective image. That is why archives typically hold multiple angles and variations: different editorial purposes demand different perspectives.

Tragedy, security, and a culture of remembrance

At this point, the tone inevitably shifts. Olympic tragedies are not “moments” in the sporting sense, but historical ruptures. They still belong to the history of the Games because they permanently changed rules, security frameworks, and public expectations.

IMAGO / Werner Schulze / The GDR relay team from right: Dagmar Käsling, Monika Zehrt, Rita Kühne, and Helga Seidler are Olympic champions in the 4x400m at the Summer Games in Munich 1972.

The terrorist attack at Munich 1972 is such a rupture. The IOC has repeatedly referred to the anniversary as the “darkest day” and has commemorated the victims in official remembrance formats. In later editions of the Games, the question of how remembrance should be made visible at the Olympics continued to be debated, including around ceremony elements and official moments of silence.

For editorial teams, these topics repeatedly raise questions of balance: How can history be shown without being instrumentalized? Here, image selection and captions must be especially precise — with a clear separation between documentation, context, and commentary. Official formats and memorial sites provide a framework, but they do not replace editorial responsibility.

This brings the story back to the earlier categories: Records and triumphs speak to “faster, higher, stronger” — tragedies remind us that the Olympics, as a global mega-event, cannot fully separate itself from political reality and risk.

How these images can be licensed legally via IMAGO

Anyone publishing Olympic icons almost always works in an environment where image rights, personality rights, and intended use must be separated cleanly. A license does not transfer ownership of an image — it grants usage rights, while copyright remains with the creator or the agency.

IMAGO offers standard licensing models on the webshop that define usage precisely:

- Rights Managed (RM): typically for clearly defined one-time uses (e.g., one article, a specific Social Media post, a defined print run). Parameters like duration, territory, and medium can be set.

- Royalty Free Classic (RF): for repeat use without per-use reporting (depending on the variant, e.g., Standard/Extended).

- Royalty Free Premium (RF Premium): for particularly flexible projects, often with a broader scope (e.g., print, campaign components, packaging — provided additional rights are in place).

Especially with sports imagery, the distinction between editorial vs. commercial use is central:

- Editorial means reporting, information, and documentation (e.g., articles, timelines, educational materials).

- Commercial includes advertising, sponsorship, product marketing, packaging, or merchandising — and may require additional permissions.

Model Release and Property Release:

If people or private locations/objects are clearly identifiable and the use becomes commercial, model releases (consent from depicted individuals) or property releases (permission from property owners, e.g., private property or artworks) can be relevant. IMAGO marks release status in metadata and supports filtering by release type.

Practical access for newsrooms and organizations

For a photo feature like the one outlined above, rights are only part of the workflow. IMAGO provides three common purchase options, depending on needs and volume:

- Webshop — Single License (internal link: IMAGO Webshop): Individual licenses for specific publications.

- Webshop — Credit Packages (internal link: Credit packages): Credits with a validity period (365 days) for regular buyers.

- Sales Manager (internal link: Sales Manager): Personal consultation for larger volumes, recurring needs, or tailored agreements.

In many editorial environments, it is also useful to review internal sections on Licenses, Rights Managed, and Royalty Free Premium to keep recurring formats consistent.

Ten moments, three categories, one shared core

The selection of the “most legendary Olympic moments” remains interpretive — but records, triumph, and tragedy provide a stable framework in retrospect. Owens, Bikila, Smith/Carlos, Beamon, Munich, Comăneci, Lake Placid, Ali, Phelps, and Bolt each represent a different facet of the Games: measurable performance, social meaning, collective dynamics, or historical rupture.

For editorial practice, these moments matter primarily because they can be told visually — as a single image, a sequence, or an archival rediscovery. IMAGO supports this work through an international, partner-based content network and clear licensing models that define usage, timeframe, and medium. And especially with Olympic material, one principle applies: care in context and rights clearance is not an extra — it is part of journalistic quality.

License Sports Images Tailored to Your Needs

Real-time editorial sports images across all major sports, including football, F1, tennis, and more, plus access to the largest editorial sports archives. Flexible licensing and fast support in Europe and worldwide.

Learn more