With back-to-back world titles in 1952 and 1953, Alberto Ascari shaped the early era of the Formula 1 World Championship like few others. At the wheel of the dominant Ferrari 500 for Scuderia Ferrari, he became a symbol of technical superiority and driving consistency. Whether as a start scene in a tightly packed field or on the podium in a red overall — these motifs embody Ferrari’s first great dominance phase in the sport’s top category.

Top 10 Formula 1 Drivers of All Time – from Fangio to Schumacher

Comparing across generations: Anyone who puts Fangio, Clark, and Schumacher side by side is not only comparing drivers, but also rulebooks, technology, race calendars, and safety standards. That’s exactly why Formula 1 rankings are never purely mathematical — they’re always an interpretation, too.

Our approach: This selection combines titles, wins, influence on driving, and the era — and puts into context how drivers performed under the conditions of their time. The structure is deliberately built for fast scanning and moves thematically from the beginnings through to the Schumacher era.

What matters in practice: For editorial teams, agencies, brands, NGOs, and educational institutions, it’s often not just the content that counts, but also the right visual language. IMAGO works with a global network of partner agencies, photographers, and archives, bundling current and historical content for licensing.

Expert guidance on races, drivers, teams, and archive material — tailored to your project.

Top 10 Formula 1 Drivers of All Time: The Short List

A timeline instead of a “points-based ranking”: The order here follows chronology — because that makes it easier to see how driving, risk, and professionalism have shifted over the decades.

- Juan Manuel Fangio (World Champion: 1951, 1954–1957): 5 titles, 24 wins in 51 championship starts; last title at age 46.

- Alberto Ascari (World Champion: 1952–1953): Back-to-back titles, a dominant Ferrari cycle in the early championship era.

- Stirling Moss (no World Championship title): 16 wins, 4× championship runner-up — often described as the “best driver without a title.”

- Jim Clark (World Champion: 1963, 1965): 2 titles, 25 Grand Prix wins overall; also won the Indy 500 in 1965.

- Jackie Stewart (World Champion: 1969, 1971, 1973): 3 titles, 27 wins — and influential as a driver who pushed safety forward.

IMAGO / Eibner / Jackie Stewart (Scotland, former world champion and racing driver), UAE, at the Formula 1 World Championship, Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, Yas Marina Circuit, 07/12/2025.

- Niki Lauda (World Champion: 1975, 1977, 1984): 3 titles, comeback after a severe accident; won the 1984 title by the narrowest margin.

- Nelson Piquet (World Champion: 1981, 1983, 1987): 3 titles, 23 Grand Prix wins; a key name of the turbo era.

- Alain Prost (World Champion: 1985, 1986, 1989, 1993): 4 titles, 51 Grand Prix wins — long the statistical benchmark.

IMAGO / Eibner / Alain Prost (France, former world champion, racing driver), UAE, at the Formula 1 World Championship, Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, Yas Marina Circuit, 07/12/2025.

- Ayrton Senna (World Champion: 1988, 1990, 1991): 3 titles, 41 wins, 65 pole positions; fatal accident in Imola in 1994.

- Michael Schumacher (World Champion: 1994, 1995, 2000–2004): 7 titles, 91 wins overall; Ferrari world champion in 2000 after 21 years.

The pioneering era — when the driver replaced the safety concept

Juan Manuel Fangio: efficiency as the currency of the 1950s

Stats that explain the context: Fangio won 24 championship races in 51 starts — a strike rate still cited today as a reference for dominance in a relatively short career. His last title came in 1957 at the age of 46, in an era when switching teams and machinery was much more part of the job than it would be later.

The 1957 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring is often cited as one of Fangio’s defining performances: strategic risk, sustained pace over distance, and near-flawless execution. Even without romanticizing it, one thing remains true: this win became a historical marker for how early Formula 1 was understood as a driver’s sport.

Alberto Ascari: dominance before “dominance” became a marketing term

Ferrari as an early power center: Ascari represents the first major championship streak of the post-war era: in 1952 he won six of seven championship races, and in 1953 more victories followed on the way to his second title. In an era with short calendars, such streaks carried a different weight than today — but they show how quickly a driver could establish himself as the pace-setter of the field.

A break in continuity: Ascari’s death in 1955 (not in a championship race) is a reminder of how thin the line was back then between elite sport and life risk. That is exactly why images from that era are often more than nostalgia for editorial teams: they are documents of a different sporting reality.

Stirling Moss: greatness without a title — and why that is possible in Formula 1

Performance beyond the championship outcome: Moss won 16 Grands Prix and finished runner-up four times. In many historical debates, he is the go-to example showing that titles are central in Formula 1 — but they don’t capture every dimension of performance (team context, reliability, strength of opposition).

Why he belongs in this top 10: Moss is not listed here as a “stand-in world champion,” but as proof that all-time lists also reflect a driver’s cultural status. He’s also a useful litmus test: if you accept Moss in a top 10, you implicitly accept that Formula 1 is more than title arithmetic.

Talent, technology, and risk — the 1960s as a turning point

Jim Clark: speed as a constant — despite unreliability

The Clark formula: Hall-of-fame summaries put his final tally at 25 wins — important context because Clark surpassed Fangio’s then-win record. At the same time, the era reflects a recurring pattern: when the car held together, Clark was often the benchmark; when it didn’t, his rivals’ machinery was.

A moment that still resonates: Clark’s 1965 Indy 500 win is more than a footnote in his profiles — it stands for a time when top drivers became icons across multiple series. For editorial use, that translates into clear visual value: Clark photos often work as a symbol of the universal racing-driver archetype of the 1960s.

Jackie Stewart: the driver as a safety advocate — and a media figure

Record and impact: Stewart combines 27 wins and 3 titles with a second layer: he pushed early and visibly for safety improvements. Hall-of-fame accounts link his role to helmets, belts, barriers, medical infrastructure — and make clear why Stewart is often ranked higher than pure statistics would suggest.

The historical backdrop: The text cites a particularly deadly period with a stark risk description (“two out of three” over five years). Even when such phrases are read as a contemporary perspective, they underscore the core issue: in the 1960s/70s, courage wasn’t just a style choice — it was part of the job definition.

Rivalries and comebacks — professionalism becomes strategy

Niki Lauda: the line between risk and calculation

Three titles, two careers: Lauda won the championship in 1975, 1977, and 1984 — and is still discussed in relation to the 1976 turning point. After his severe Nürburgring crash, he returned in the same season; hall-of-fame narratives connect that to a career increasingly shaped by analysis, discipline, and teamwork.

The closest finish as a motif: For 1984, the key point is that Lauda won the title by the smallest possible margin; retrospective accounts cite the famous half-point as the difference. That’s more than trivia: it shows how, in modern Formula 1, even small regulatory and results details can decide a driver’s career stature.

IMAGO / Sven Simon / Podium ceremony, Austrian Grand Prix in Zeltweg 1984, left to right: FISA President Jean-Marie Balestre (France), Nelson Piquet (Brazil, Brabham BMW), winner Niki Lauda (Austria, McLaren TAG Porsche) and Michele Alboreto (Italy, Ferrari), Formula 1 World Championship.

Three titles in a turbulent era: Piquet won the championship in 1981, 1983, and 1987. A Formula 1 retrospective also credits him with 23 race wins — placing him among the few drivers with three or more championships.

Why Piquet matters in this story: He represents a phase where Formula 1 was more shaped than ever by technology leaps (turbo), team dynamics, and internal power struggles. That makes Piquet especially useful in an all-time piece to ask whether “greatness” must equal popularity — or whether it is sometimes simply quality of results.

Alain Prost: the engineer among champions

Numbers that define an era: Prost won four titles and collected 51 Grand Prix wins. For a long time, that made him the statistical reference point — until later eras opened up new dimensions of records.

Prost vs. Senna as an interpretive lens: In historical narratives, Prost is often the driver associated with “intelligent racing” — methodically collecting points, minimizing retirements, and managing risk. This kind of greatness is less photogenic than “one lap for eternity,” but it’s central to team culture and championship logic.

Ayrton Senna: qualifying culture, searching for the limit, and the 1994 rupture

Measurable excellence: A Formula 1 retrospective credits Senna with 41 wins and 65 pole positions (1984–1994). That matters for his ranking because it captures two kinds of strength: race control and maximum single-lap pace.

The rivalry factor: Senna hall-of-fame accounts point to the Suzuka collisions in the title years 1989 and 1990 as part of the Prost–Senna conflict. To this day, it’s a case study in how all-time evaluations also depend on whether you see such moments as consequence or overstepping the line.

The rupture: Senna died at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix in Imola. In any top-10 discussion, this isn’t pathos — it’s a factual event with consequences: the sport changed structurally, and the perception of “risk as part of the show” was permanently corrected.

Schumacher — dominance as a system of driver, team, and process

Michael Schumacher: records, controversies, professionalism

The statistical frame: Schumacher won seven world championships and ended his career (as of the end of 2006) with 91 wins. Hall-of-fame narratives frame him as a driver who shaped “almost every” scoring chapter — not just titles, but repeated maximization across seasons.

The Ferrari turnaround: When Schumacher joined Ferrari in 1996, the team had not had a drivers’ champion since Jody Scheckter in 1979. In 2000, Schumacher became Ferrari’s first champion in 21 years, then won four more titles in a row (2000–2004). This chain is less “one man beats everyone” and more a case study in how Formula 1 became organized high performance.

The gray areas belong to the assessment: Hall-of-fame narratives openly note that Schumacher’s ethics were debated at times (including Adelaide 1994 and Jerez 1997, with a 1997 sanction). For a neutral top-10 view, this is essential: greatness in Formula 1 is historically often not free of controversy — and that’s precisely why performance and evaluation must be kept distinct.

10 motifs for a journey from Fangio to Schumacher

An image idea, not a claim: The motifs below are phrased so they work as search queries and captions. IMAGO bundles motorsport content from partner networks and archives; whether a specific motif is available depends on inventory, date, photographer, and license status.

Image 1 – Fangio in the Mercedes W196, 1954/55.

Five-time Formula 1 World Champion Juan Manuel Fangio defined the 1954/55 season in the legendary Mercedes-Benz Formula 1 World Championship with the technically revolutionary Mercedes-Benz W196. Whether as a focused driver portrait in the silver racing suit or a dynamic on-track shot with the distinctive streamlined bodywork — images from this era symbolize precision, dominance, and the “Silver Arrows” myth.

IMAGO / Thomas Zimmermann / This photo was taken on 16/08/1986 during a demonstration run with Fangio at the wheel on the Nürburgring as part of the Oldtimer Grand Prix. Fangio became world champion in 1954 and 1955 with the W196.

Image 2 – Ascari and Ferrari dominance, 1952/53

IMAGO / Thomas Zimmermann / Ferrari Monoposto 3400cc from 1951 at a vintage race. Alberto Ascari won the world championships in 1952 and 1953 with Ferrari.

Image 3 – Moss as “Mr. Monaco”: Action shot on a tight street circuit

Nicknamed “Mr. Monaco,” Stirling Moss became an icon of the tight Monaco Grand Prix street circuit — especially his 1961 victory is often seen as a driving masterclass between guardrails and the harbor. Alternatively, an action shot in the cockpit of the Mercedes-Benz W196 conveys the technical elegance and precision of the Mercedes era: focused gaze, a narrow racing line, maximum control in minimal space.

Image 4 – Clark in the Lotus 25

With the revolutionary monocoque chassis of the Lotus 25, Jim Clark dominated the 1963 Formula 1 World Championship season. A classic onboard or side profile — for example at Silverstone Circuit or on the high-speed Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps — highlights the lightness and precision of this milestone in racing technology.

IMAGO / Horstmüller / Formula 1 race, German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring on 02/08/1963. Jim Clark in the Lotus 25.

Image 5 – Stewart in the Tyrrell/Matra, 1969–1973.

With his distinctive helmet design and black cap, Jackie Stewart became the face of a new, professional Formula 1 era between 1969 and 1973. In the Matra MS80 he won the title in 1969; further success followed later with Tyrrell Racing in the Tyrrell 003. Whether as a dynamic race scene or an iconic paddock portrait — Stewart stands for speed, style awareness, and the beginning of a consistent safety movement in the Formula 1 World Championship.

IMAGO / Pressefoto Baumann / Jackie Stewart (Scotland, left) and his teammate François Cevert (France, Tyrrell Ford) clean their visors, 1973.

Image 6 – Lauda 1976 (comeback narrative): race scene 1976/77.

The 1976 season made Niki Lauda a symbol of discipline and mental strength. After his severe crash on the Nürburgring Nordschleife, he returned to the cockpit of the Ferrari 312T2 just a few weeks later, shaping one of the most striking comeback narratives in Formula 1 World Championship history. Whether as a focused paddock portrait with bandages or as a race scene from 1976/77 in the red Ferrari — these motifs stand for professionalism, risk awareness, and the dramatic intensity of that season.

IMAGO / Thomas Zimmermann / Carlos Reutemann + Niki Lauda, Team Ferrari in Zandvoort, both in the Formula 1 Ferrari 312 T2, Dutch Grand Prix 1977. Niki Lauda won the race.

Image 7 – Piquet in the turbo era

As a three-time world champion, Nelson Piquet embodied the uncompromising turbo era of the 1980s. In the radical Brabham BT52 with a BMW turbo engine, he won the 1983 title; later he triumphed with Williams. An action shot with wide slicks, angular aerodynamics, and typical 1980s color aesthetics conveys the raw power delivery and the technical arms race of that era in the Formula 1 World Championship.

IMAGO / Thomas Zimmermann / The Brabham BT52, driven in the 1983 season by Nelson Piquet (pictured). The photo was taken at the 1983 Italian Grand Prix in Monza. Piquet won the race and secured his second world title — the first time in Formula 1 history with a Brabham-BMW.

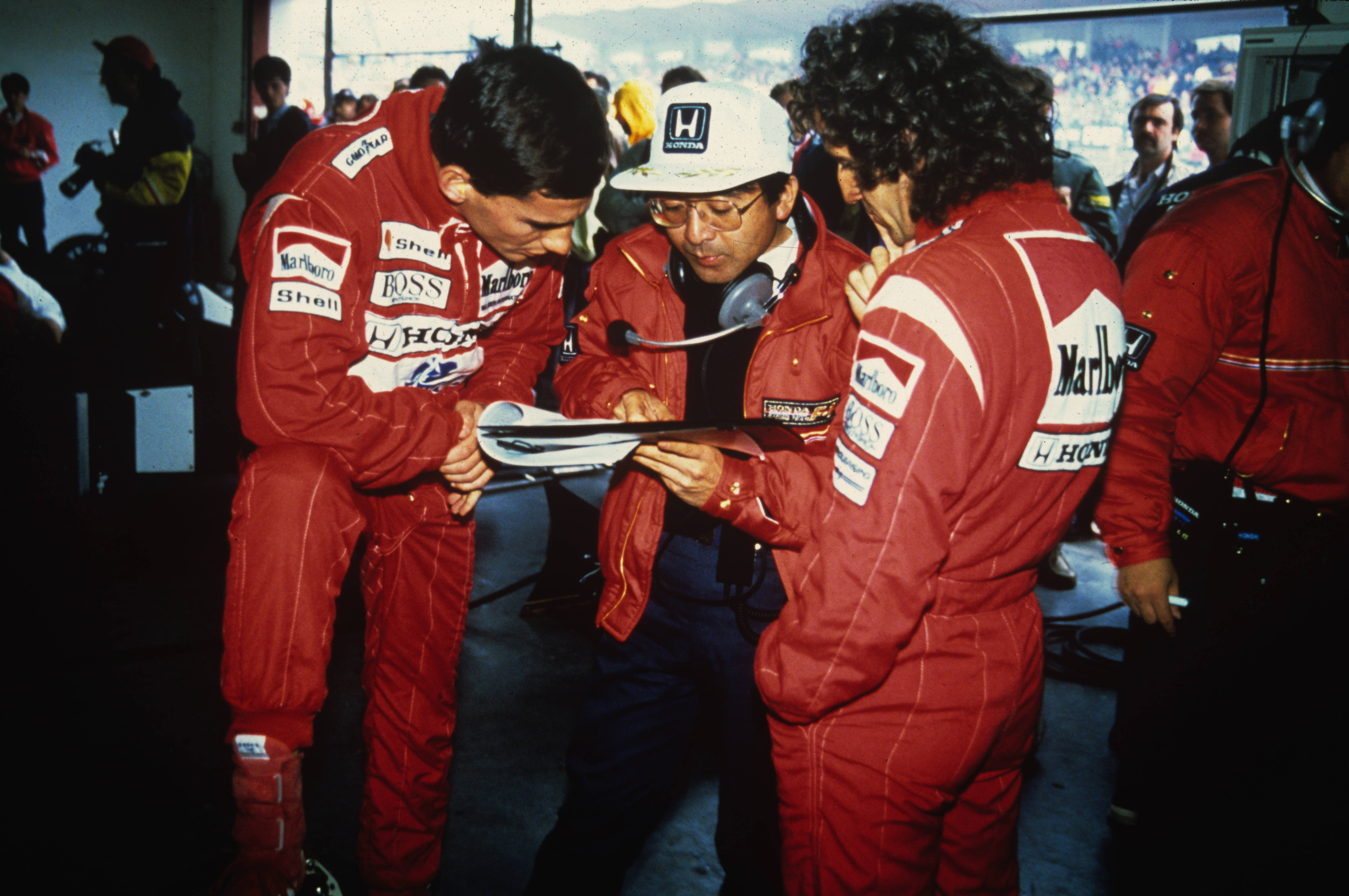

Image 8 – Prost as a “points racer”: Calm podium scene or a pit photo that suggests strategy.

Alain Prost was considered a master of strategy — coolly calculating, low on errors, and always focused on maximum return. Whether a calm podium scene or a concentrated pit-lane photo in conversation with engineers at McLaren — such motifs underscore his reputation as a “points racer.” Prost won four world championships in the Formula 1 World Championship and still stands for tactical intelligence in an era of intense team and engine rivalries.

IMAGO / Visions In Golf / Alain Prost, 1988, known as “The Professor” for his calculated driving style, is a legendary figure in Formula 1.

Image 9 – Senna: pole-lap iconography

Hardly any driver embodies qualifying intensity as vividly as Ayrton Senna. At the wheel of the McLaren MP4/4, he dominated qualifying in 1988 with almost iconic precision. A pole-lap shot with minimal steering input and maximum focus — or an intense portrait with the visor down — conveys the concentration that made Senna a defining figure of the Formula 1 World Championship.

IMAGO / WEREK / Podium ceremony, German Grand Prix 1989 — winner Ayrton Senna (Brazil, McLaren Honda, center) with Alain Prost (France, McLaren Honda, left) and Gerhard Berger (Austria, Ferrari).

Image 10 – Schumacher and Ferrari, 2000–2004

Between 2000 and 2004, Michael Schumacher and Scuderia Ferrari shaped one of the most dominant phases in the Formula 1 World Championship. Whether a title-deciding moment with arms raised, podium celebrations, or close collaboration with engineers — motifs from this era stand for perfection in the interplay of driver, team, and technology. Cars like the F2002 or F2004 became symbols of an unprecedented winning streak.

IMAGO / Kräling / Podium ceremony after the Japanese Grand Prix in Suzuka 2004: winner Michael Schumacher (Germany, Ferrari) and Jenson Button (England, BAR-Honda, behind).

How IMAGO makes motorsport images properly licensable

When you “buy” an image, you generally do not acquire ownership of the motif, but a clearly defined usage license. Copyright remains with the rights holder; the license specifies precisely for how long, where, in which geographic area, and for what type of use an image may be used. This is how IMAGO creates transparency and legal certainty for editorial teams, brands, agencies, and businesses.

Overview of license types

IMAGO offers different licensing models that can be selected depending on project requirements:

- Rights Managed (RM):

Often used for one-off or clearly defined editorial use such as news articles, blogs, or social media. Variants like Standard, Extended, or Enterprise differ in scope of use. - Royalty Free Classic (RF):

Depending on the motif, usable for editorial and commercial purposes, usually without mandatory per-use reporting. Standard and Extended licenses vary, among other things, in reach, circulation, and advertising use. - Royalty Free Premium (RF Premium):

For projects with increased usage needs — such as print, advertising, packaging, or merchandising. The decisive factor is always the specific license definition for the relevant content.

Model and property releases: crucial for commercial use

As soon as usage becomes commercial, so-called releases play a central role:

- Model Release: A written consent from the depicted person for commercial uses such as advertising, marketing, or corporate communications.

- Property Release: Required when recognizable property — such as buildings, artworks, or private objects — is used commercially.

Rule of thumb: without the relevant releases, image material is often only usable editorially, sometimes with additional restrictions. IMAGO lists release information and usage notes in metadata and supports targeted research via filter functions.

Three ways to find suitable Formula 1 images

For editorial teams and brands, there are different access routes:

- Webshop – Single License: Individual images can be licensed directly (RM or RF Classic/Premium). Registration or guest checkout are possible.

- Webshop – Credit Packages: Credits with 365 days of validity are suitable for regular needs and, according to IMAGO, may offer savings compared with single-image licenses. This model is available to registered users.

- Sales Manager: For larger volumes, special use cases, or individual contract models — including personal support with research and processing.

The “Top 10 Formula 1 Drivers of All Time” — from Juan Manuel Fangio to Michael Schumacher — stand not only for individual achievements, but for the evolution of the Formula 1 World Championship itself.

Fangio and Ascari mark the pioneering era; Clark and Stewart the turning point between talent and growing safety awareness. Lauda, Piquet, Prost, and Senna embody rivalries, the turbo era, and strategic finesse — while Schumacher stands for the professionalization and industrialization of modern dominance.

For image selection, that means: not every icon is best represented by a victory pose. Often pit-lane scenes, helmet portraits, grid lineups, or historical track views say more about an era than the podium moment. IMAGO supports such visual narratives with clearly defined licensing models, transparent release information, and flexible purchasing options — from single images to project-specific support.

License Sports Images Tailored to Your Needs

Real-time editorial sports images across all major sports, including football, F1, tennis, and more, plus access to the largest editorial sports archives. Flexible licensing and fast support in Europe and worldwide.

Learn more